Learn the amazing, obscure story of Josef Ganz…

For some time after the close of World War II, the world largely believed Ferdinand Porsche was solely responsible for the development of the Volkswagen Beetle. However, a Jewish engineer in Germany was the real source of the design for the “people’s car” which eventually would provide cheap personal transportation not only for Germans, but people all over the globe.

Learn about Henry Ford's bizarre social program to control his workforce here.

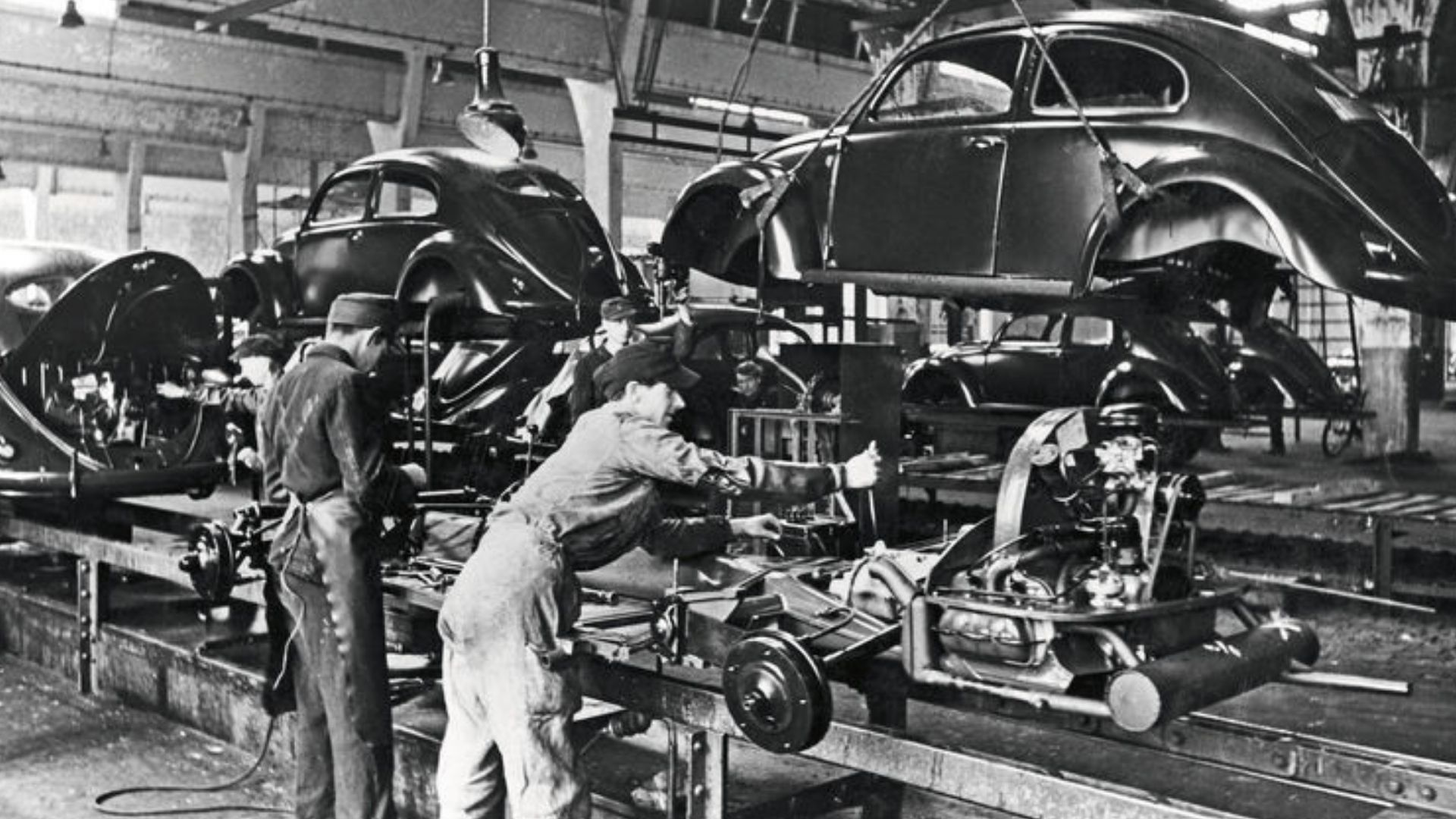

This much-forgotten Jewish engineer was named Josef Ganz. As you might imagine, Hitler and the Nazi regime didn’t want one of their nationalist socialist dreams exposed as being originated by a Jew since that would hardly support the despicable theory of Aryan superiority and Jewish inferiority. For that and other reasons, Porsche was tapped to make the Volkswagen a reality, although the war effort derailed production entirely.

Watch the Motorious Podcast here.

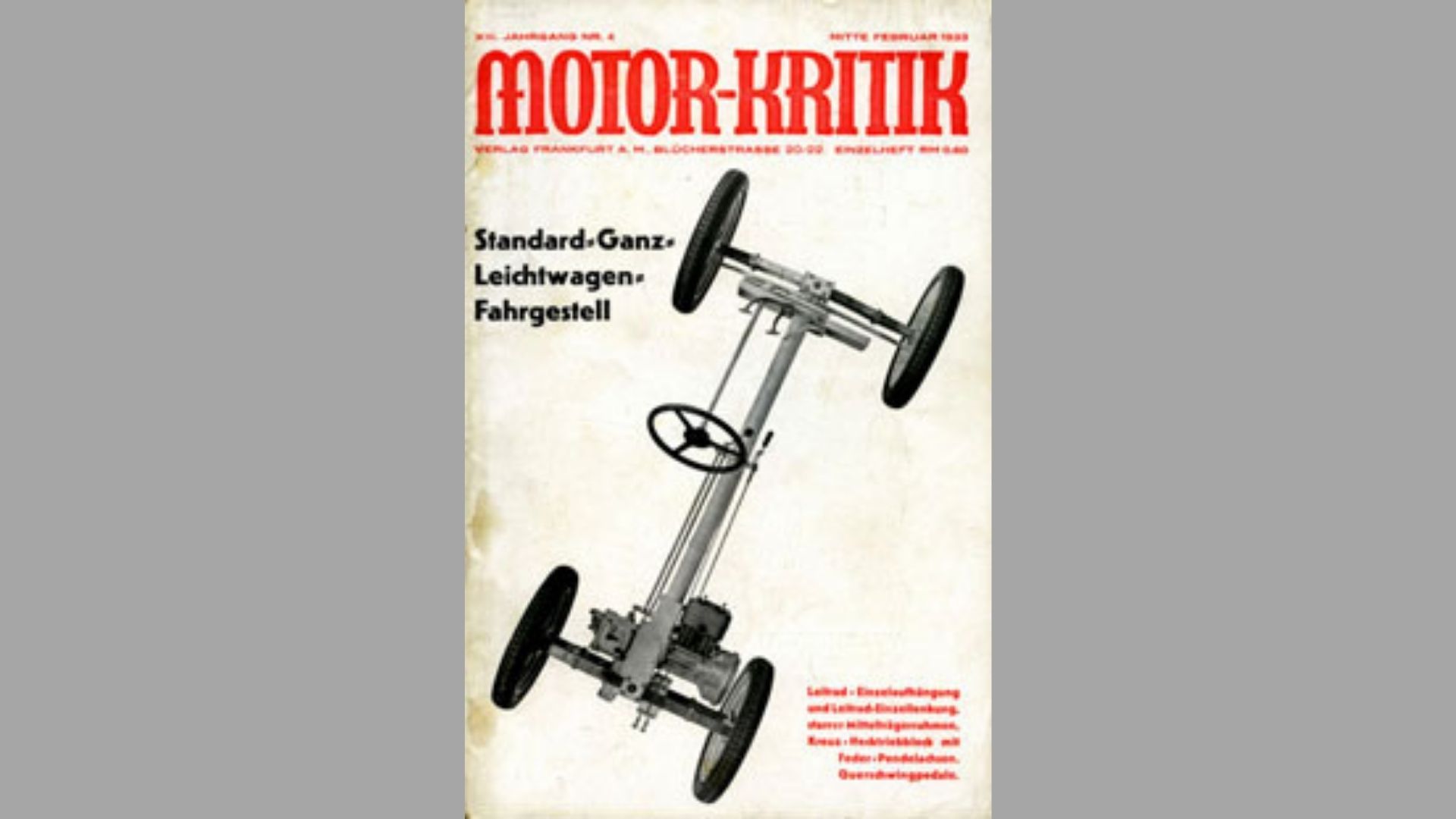

Ganz, who not only was an engineer but was also the editor in chief of German automotive magazine Motor-Kritik, was a true visionary. The man was extremely critical of the German auto industry, using his publication to assail German automakers with accusations of being anti-progress as they created cumbersome, overly expensive cars priced only for the elite.

Like Hitler, Ganz had profound respect for Henry Ford and his Model T, the automobile which provided so much freedom of movement for Americans. He set out to create his own revolutionary people's car, which he insisted must have the engine in the rear, a backbone chassis, swing axles, four wheels, and a streamlined body. Ganz regularly used Motor-Kritik to preach these ideas, irritating his rivals in the industry. However, some listened and began trying to adopt at least portions of Ganz’s Volkswagen. One reader became ardently dedicated to seeing the concept become reality. That reader was, of course, Adolf Hitler.

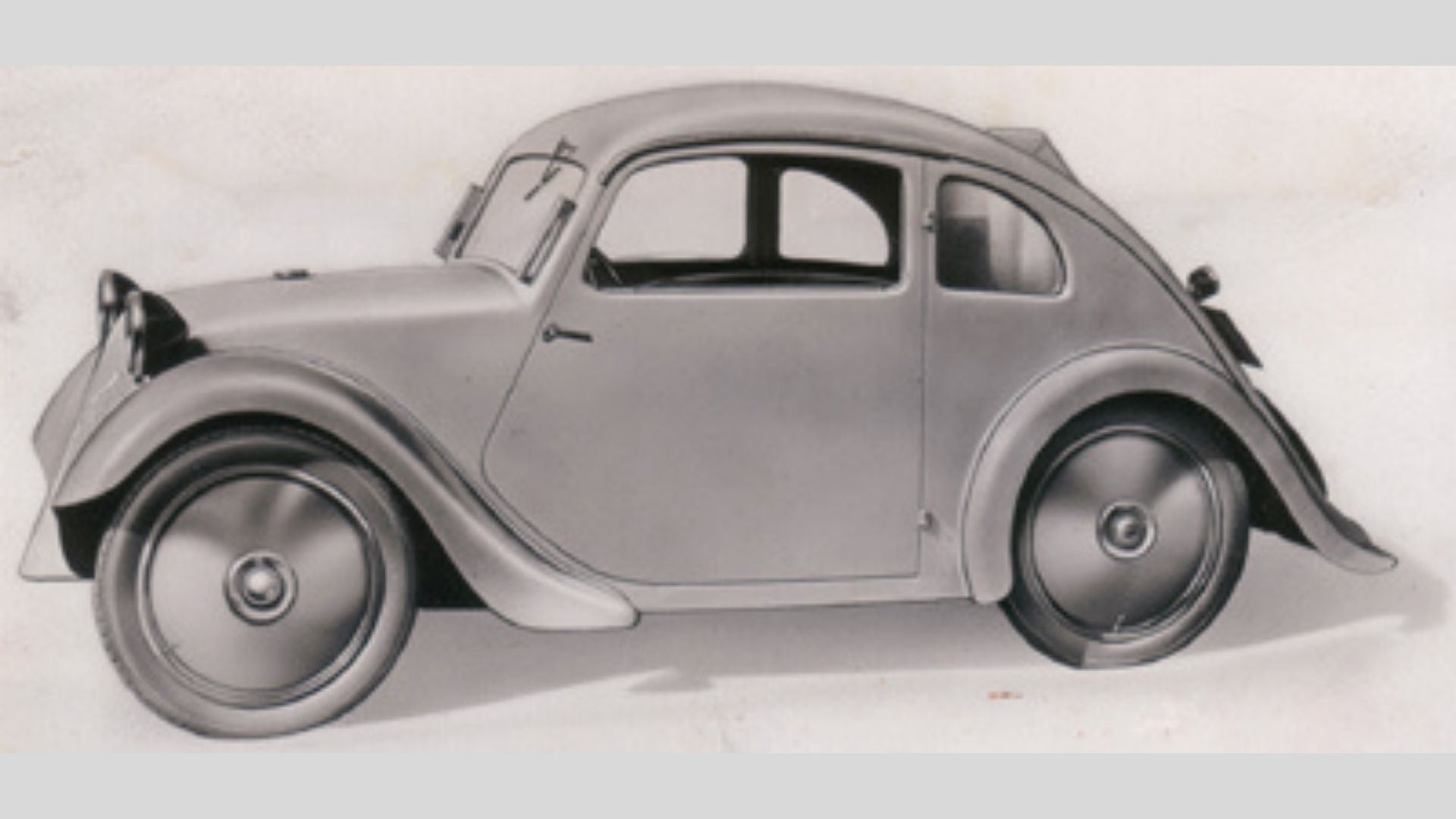

As you might imagine, many in the automotive industry didn’t take too kindly to Ganz’s assailing criticisms. Instead of trying to adapt, they decided to discredit him and bury the journalist/engineer in legal proceedings. Ganz claimed some rivals stole designs and filed patents to block him from producing his Volkswagen. Despite these efforts, Ganz enjoyed enormous influence in the industry, working with automakers like Mercedes-Benz, Standard, and Adler to produce several vehicles based in part on his ideas. Among these were the Mercedes-Benz 170 and 120H as well as the Standard Superior.

Others were influenced by Ganz’s concepts, although they put their unique spin on their creations. One such product was the Zündapp Type 12 designed by none other than Ferdinand Porsche. While the car never made it past the prototype stage, it used many of the principles preached in the pages of Motor-Kritik.

On his own, Ganz continued to develop his dream Volkswagen. One of the prototypes, the May Bug, he proudly showed off to other members of the press, including holding a demonstration of how it could drive underneath a truck trailer, as if that were something safe to do. While being a gifted engineer, Ganz was oftentimes reckless when testing out his and other’s vehicles, resulting in him being injured in more than one incident. He also sometimes ruined relationships in similar fashion, like when he used the pages of Motor-Kritik to claim the Standard Superior was his creation transformed into an “almost feudal vehicle.”

As Hitler became chancellor without being elected and the bombastic leader began solidifying Nazi control of the country through intimidation and violence, it became open season on Jews. However, Ganz was excitedly fixated on Hitler promoting the idea of a Volkswagen with all the elements Ganz had promoted, and at an affordable price. That, combined with a new highway system, would give Germans personal mobility on a scale like what Ford’s Model T did for Americans. Ganz’s dream was finally starting to come true and he had the Fuhrer to thank.

When the chancellor attended the 1933 IAMA, the international motor show, in Berlin less than two weeks after he was sworn into office, Hitler delivered a fiery speech in which he thanked the industrialists, technicians, and designers for their efforts to provide better, more affordable personal transportation to the German people. Ganz took the thanks as being directed straight to him. He had high hopes the Nazi leader would finally see his vision of a Volkswagen turned into reality.

However, Ganz’s rivals conspired against him. One even joined the infamous SS, using his position to drum up charges and have Ganz imprisoned. Eventually he was freed but still tried fighting mounting legal challenges through his attorney. It was only when he was outside of the country that he realized his enemies were intent on having him sent to a concentration camp. Risking it all, Ganz snuck back into the country to retrieve his many sketches and other critical paperwork in a daring mission. For the remainder of the war, Ganz spent his time in neutral Switzerland.

The persecution of Ganz didn’t stop with the defeat of Germany in the war. Even though he was living in Switzerland where he was working on creating a “Swiss Volkswagen,” some former Nazi officials who escaped legal prosecution launched a smear campaign against him once more. Ganz was accused of being a communist secret agent, violating patents, etc. One reporter went so far as to characterize Ganz’s legal problems as so large and complex they “threatened to paralyze the entire judiciary” of Switzerland.

Eventually, the persecution in Europe was so severe Ganz fled to Australia. Working in a rubber factory and later for Holden, he made small engineering contributions, but nothing like the Volkswagen from his prime. Eventually, Volkswagen offered him a pension for his work on the Type 1. His health failing, Ganz died in Australia, his legacy and contribution to the Volkswagen Beetle largely obscured to the world.

For those who would judge Ferdinand Porsche and his role in bringing about the Volkswagen harshly, keep in mind after the war was over Ganz met with Porsche in Geneva, where they talked about their latest engineering work. Ganz said the other engineer looked like he’d “been through a great deal.” That’s understandable considering Porsche and his family fled to France as the Third Reich fell, only for a leadership change in the country to lead to legal prosecution of Ferdinand. He served 22 months in prison before being released. The two men parted ways on good terms, so Ganz held no ill will toward Porsche. Both men had been victims of a totalitarian regime, having done what they thought necessary to make it through the horrendous ordeal.

Source: The Extraordinary Life of Josef Ganz: The Jewish Engineer Behind Hitler's Volkswagen by Paul Schilperoord