Yes, these really did happen…

The history of motorcycles is filled with all kinds of oddities, from board track racing to a Harley-Davidson which was designed to be steered from the sidecar. Another strange aspect of the past is the motorcycle chariot races.

Yes, as unbelievable as that sounds, starting in the 1920s people would strap motorcycles to a chariot as if they were horses, then race against similar setups on a dirt track in a large stadium with throngs of cheering crowds. If that sounds like some strange Roman game, there’s good reason since inspiration for these odd competitions came from a movie set in Rome.

It was Australia of all places which first invented this admittedly dangerous and incredibly cool form of motorsport, although people in New Zealand, the United States, and Europe claim they started the trend. With the success of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ in 1925, people were absolutely fascinated with everything about it, including the exciting chariot race sequence. With the public thirsty for more of that kind of action, someone saw an opportunity to use modern technology to really amp things up.

Riders would don all kinds of Roman-like costumes to wow the crowds, including robes which would dramatically flow behind them as they sped around the dirt track. They would also wear helmets with stylized finishes to imitate the movie’s costumes. Julius Caesar and Mark Antony were often the only two characters racing, but sometimes they mixed things up and had more people and different characters at the helm.

Sometimes these events would be held at wood tracks, which obviously added to the challenge. One such location was the old Charlotte Speedway, which was constructed back in 1924.

The thing is with the motorcycle chariots, the riders would be able to accelerate faster since they would be using more than one motor. That made it quite the spectacle to watch versus regular motorcycle races. The setup supposedly increased maneuverability, or at least that’s the claim, although we think that one is pretty bogus.

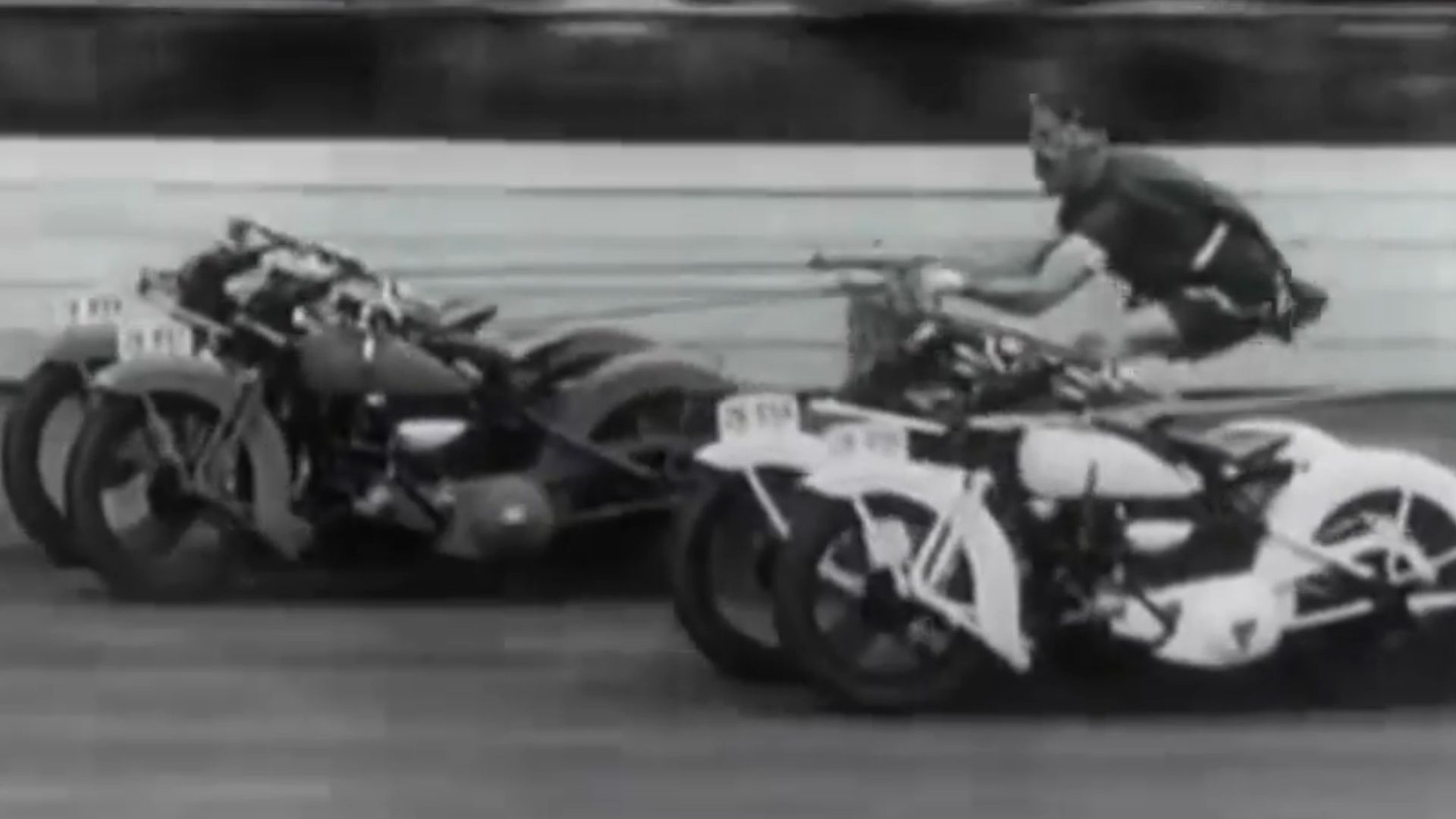

Methods for attaching the motorcycle(s) to the chariot seem to have varied greatly. If multiple motorcycles were used, they sometimes would be joined together with welded pipes, which seems like it would prevent one straying to far one way or the other.

If you think motorcycle chariot racing was a dangerous sport, you’re correct. While there isn’t much information today about crashes during these events, and in fact there isn’t much information period, the details of how riders would steer their valiant steeds is enough to make most people cringe. They would tie ropes to the bikes’ handlebars and pull on them, an imprecise and difficult way to maneuver a motorcycle for sure. One can’t help but think that was intentional as a way to make the races more exciting for the crowds, since defying death can be a real draw.

In some versions of the motorsport, riders would be on the motorcycle(s) and in the chariot. The man in the chariot would work ropes which were tied to the motorcycle rider’s arms, apparently directing him instead of letting the man steer by himself. This is troubling and hilarious on many levels.

There’s evidence these motorcycle chariot races were popular well into the Great Depression. Often the races were accompanied by other events, like a parade, trick motorcycle riding/dangerous stunts, plus clowns, trained dogs, etc. These were quite the community events and in the days before television, streaming services, and other modern entertainment options it’s easy to see why they’d be so popular. While not entirely clear, it seems the troubles of WWII not only ended the motorcycle chariot races but also virtually wiped away memory of their existence.

Some people are trying to bring them back in the modern age, complete with some modern twists like minibikes, although they are admittedly few and far between. With our high-brow sensibilities and propensity to find error in everything, reviving something like this could prove to be impossible, but there’s still hope.